Riding a Unicorn (Part 1)

Peace be upon you, fellow digital wanderer.

I’ve written this story once before, but I no longer have access to it. On my last days at Grab, I wrote down my recollections in a Google Doc, one final farewell shared with close colleagues. That version is now locked away in the company’s Google Workspace, beyond my reach.

Back then, I barely had time to reflect. Now, I do, and I intend to make the most of it. This will be a multipart series, and I’ll do my best to make it entertaining—though some parts may be dramatised for effect.

Here is a deep dive into my memories as a Software Engineer at MyTeksi/Grab — a memory-mining exercise. This isn’t the definitive history of Grab, just my version of events. My story is no more important or accurate than anyone else’s. I wouldn’t dare to claim this is exactly how things happened, but I can confidently say this is how I remember them.

For those unfamiliar, Grab (originally called MyTeksi) was a promising e-hailing start-up that achieved unicorn status and later went public on Nasdaq. It became the market leader across Southeast Asia, and I had the privilege of being part of that remarkable journey. I joined when the company was a scrappy start-up and stayed until it IPO-ed. It was a wild nine-year ride.

You won’t find deep technical breakdowns, no detailed accounts of how Grab scaled to millions of rides per day, or how we migrated from a monolithic Ruby on Rails architecture to a Go-based micro-services system. For those, the Grab Engineering blog has plenty of well-written posts.

I’m here to write about the shenanigans, the highs, the lows, the memorable moments. I started sometime in 2012–2013, as an external contractor, officially joined around 2014, and left at the end of 2023. Along the way, I worked in multiple Grab offices, each marking a distinct chapter of my journey. And that’s how I’ll be telling this story.

MyTeksi office at PJ (Renault showroom)

I know that MyTeksi started out in a tiny storage-room-sized office somewhere in Segambut, I’ve seen photos of it. The real OGs sometimes tell stories about those early days: a few laptops, some inexpensive smartphones, and a bold idea. Who would have thought that, one day, smartphones would replace the in-car push-to-talk radios used in taxis?

Back in the pre-mobile internet days, taxi dispatching in Malaysia (and likely elsewhere) relied on in-car push-to-talk radios (VHF/UHF, CB? I’m not too sure). Passengers would call a cab service, tell the operator their pickup and drop-off locations, and the operator would then broadcast the job over a shared radio frequency. Any driver within range who wanted the job would respond via radio, and the operator would assign it.

It was a complex system. Taxi call center operators functioned like air traffic controllers, coordinating an entire fleet in real time. But the system was far from efficient. Operators had no way of knowing if a driver was actually nearby or halfway across the city. Passengers were left in the dark, anxiously waiting for their ride. Many would call back, prompting the operator to radio in again and ask the driver for an update.

Since the initial job broadcast went out to all drivers, some would "snipe" others’ jobs, knowing exactly where to pick up the passenger before the assigned driver could get there. It was chaotic, slow, and imprecise.

The Interview

MyTeksi was still in stealth mode while operating out of its Segambut office. But that wasn’t where my journey with them began. My story started at their Petaling Jaya office, on the floor above a Renault showroom.

I remember walking past the gleaming Renault cars, then finding a small side staircase that led up to the upper floor. The office, before it was renovated, had an unmistakably dull look. Grey carpets, grey tables, grey walls, some of them plastered with sticky notes. It felt like no one really cared about office aesthetics back then. The only priority was getting things done.

The space was open-plan, with tables grouped together into islands. One cluster had people hunched over laptops, some talking, others on the phone. The group I was directed to had a different energy, each desk had an external monitor, laptops plugged in, everyone locked in. This was the original ‘tech island’.

The moniker ‘tech island’ lived on as a Slack channel long after those early days. It survived the migration from HipChat to Slack, becoming an infamous hangout where devs shared memes and messed around. I can’t say if the channel still exists, but when I left at the end of 2023, it was still active—memes still flowing.

I was there for an interview. A software developer role.

I didn’t get the job.

I joined a digital agency that back then was doing microsites ad campaigns for brands like Nissan and KFC. I’ve always wanted to be a developer, to do something with code.

My first job after university was with a defence contractor. It was mostly an IT support role, dealing with enterprise solutions for the armed forces. I did manage to write some code while working with their Special Projects division, but it wasn’t enough. I wanted more.

Back in university, I devoured every story I could find about Silicon Valley startups, the legendary garages, the late-night coding marathons, the breakthroughs that turned scrappy teams into giants. I romanticised that world, imagining myself in it, building something revolutionary. I had always dreamed of joining (or starting) a tech startup. I had a few failed attempts, but that’s a story for another time. (Subscribe to my newsletter. One of these days, I might just write about it.)

The digital agency, EzyPzy it was called, were close friends with MyTeksi the startup. In those early days, MyTeksi outsourced a few features to EzyPzy, and that’s how I got my first real taste of working with them.

Web to SMS booking

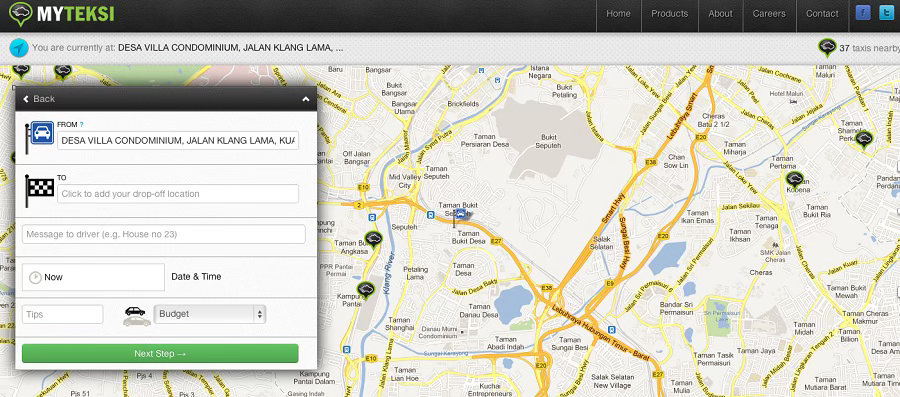

The first thing I worked on was revamping the MyTeksi website, a full-page Google Map with a simple taxi booking form. You entered your pick-up point, drop-off point, and mobile phone number. Once a taxi was allocated to you, you’d receive an SMS with the taxi’s plate number.

This was around 2012–2013. Smartphones were still relatively new. BlackBerry was hanging on, and Nokia was still in the game. While iPhones and Android devices had entered the market, most people were still using basic GSM phones or one with the Symbian OS. I was one of them—rocking a Nokia Asha 210. I wanted a phone with a QWERTY keypad but couldn’t afford a BlackBerry.

The web-to-SMS booking flow wasn’t exactly revolutionary. From a passenger’s perspective, it wasn’t much different from calling a taxi company and anxiously waiting for the driver to arrive. No real-time updates. No way to know if the driver was near or far.

But on the taxi operator’s side, it was a game-changer. The system eliminated the back-and-forth chatter of walkie-talkies. Instead of dispatchers blindly assigning jobs, we had a service that could allocate jobs to nearby drivers, who could then bid to accept them. Drivers received job details through an Android app, which also sent constant location updates over 3G.

The web booking flow was short-lived. The feature was scrapped as MyTeksi went all-in on mobile apps. At the time, I wasn’t convinced it was the right move—it felt like we were cutting off a huge portion of users. Smartphones were expensive. Mobile data—EDGE and 3G—was expensive. These were luxuries that many simply couldn’t afford. MyTeksi subsidised some taxi drivers with smartphones, but there was no way to subsidise passengers. I didn’t even have a smartphone myself.

Perhaps Anthony Tan (co-founder and now CEO of Grab) and the MyTeksi leadership saw what the rest of us didn’t, that a paradigm shift was coming. The smartphone revolution was upon us. And looking back, who would’ve thought that today, it’s almost impossible to find someone without a smartphone?

Here is a video demo of the early version of the app.

Share My ride

The second feature I helped build was “Share My Ride.” At the time, safety was one of MyTeksi’s biggest selling points. The idea was simple: once you got a ride, you could send an SMS with a web link to your loved ones. That link opened a webpage showing the real-time location of your driver for that particular booking.

This way, your loved ones could see if the driver was going off course. And more importantly, the driver knew they were being tracked—no unnecessary detours.

Technically, it was dead simple to implement. The link contained the booking ID. I built a full-page Google Map that periodically made an AJAX call to the backend, fetching the driver’s latest longitude and latitude based on that booking ID. The page then updated the marker on the map with each new location, making it look like the car was moving in real time.

I remember how futuristic it felt—like something straight out of a spy movie. You know those scenes where an agent plants a tracker on a car and watches it move across a digital map? That’s exactly what this felt like. Today, it’s standard, but back in 2012–2013, this was straight from the movies.

What impressed me even more was how simple it was. When I worked for a defence contractor, tracking military vehicles required expensive hardware and high-end enterprise IT systems. And here was a small startup, using cheap smartphones and a Node.js backend, tracking fleets of taxis just as effectively.

Sure, today, it seems obvious to use smartphones for real-time tracking. But back then? Smartphones with GPS and geolocation capabilities were still a new concept. And we were making it work with nothing more than standard web tech and some clever engineering.

Office Renovation

As a contractor, I had only worked on the frontend of things. For both Web to SMS booking and Share My Ride, I didn’t touch any backend code. The endpoints were already set up for me—I just had to consume them.

But after a few months, that changed. I was no longer a contractor, I was part of the team now. I had GitHub issues assigned to me, and attended sprint meetings to see them move Trello cards across the board.

Around the same time, the office space on the upper floor of the Renault showroom got a makeover. The dull, grey workspace was transformed into a sleek, modern office with MyTeksi’s signature green and black decor.

There was a common area with a comfy couch where people hung out. The meeting rooms had glass walls, making every discussion feel like a high-stakes strategy session. The old grey wall covered in sticky notes? Replaced with a huge whiteboard, where engineers like to draw squares boxes, and arrows pointing in every direction.

Here is a video I found on YouTube by the interior designer that transformed the space.

By this time, I had started working on the backend and the back-office system. It was a Ruby on Rails application that served APIs for the Passenger app and server-rendered pages for internal back-office work.

On the driver side, we had a Node.js service maintaining a socket connection to the Driver app. To pass messages between applications, we used a Redis queue of sorts. Nothing groundbreaking, but it got the job done.

Well, most of the time.

Black Thursday (or was it Friday?)

I remember the day someone showed us a tiny newspaper clipping from a Singaporean newspaper. It wasn’t front-page news—just a small section buried in the back pages. It mentioned that GrabTaxi was down for a few hours and that taxi drivers were complaining.

By this time, MyTeksi had expanded to neighbouring countries. While we still operated as MyTeksi in Malaysia, elsewhere, we were branded as GrabTaxi. Back then, we were only handling taxis, private cars weren’t a thing yet.

The team had mixed feelings about the news clipping. On one hand, we were kind of proud, our downtime was newsworthy! People actually noticed when our system was down. On the other hand, people actually noticed when our system was down. And it was happening way too often.

System stability had become a huge problem. It had become our top priority.

Which brings us to Black Thursday (or was it Friday? Or Saturday? My memory’s fuzzy). That weekend, the entire team was holed up in the office, frantically debugging. The backend couldn’t handle the flood of booking requests, and the system was constantly going down.

The whiteboard was covered in a laundry list of bugs and production issues. We had to fix everything, deploy a new backend, and probably migrate the database too. Hopefully to something more stable than the mess we had before.

At this point, I’m not entirely sure if I was still a contractor or had already joined full-time. The timeline is a bit of a blur. What I do remember is offering to help in any way I could. I wasn’t a 10x software engineer wizard, but I was competent enough to tackle some issues on the whiteboard. So I hunkered down with the rest of the engineers and got to work.

That night, the camaraderie between engineers, designers, marketing, and customer service stayed with me. The vibe wasn’t hopelessness, it was determination. Instead of despair, there was a shared resolve to push through. The shared purpose united everyone, transforming what could have been defeat into a rallying moment that defined the team's spirit moving forward.

The new code changes need to be tested before it gets deployed. However, we didn’t have a QA team back then, so testing was usually done by the developers themselves. But that took time, and we needed devs to move on to the next batch of fixes.

Late that night, while on my way to grab another can of Red Bull, I passed by one of the meeting rooms. Inside, the UI/UX design team had set up shop, not to work on new app designs, but to QA the changes pushed to staging.

Every time a fix was pushed to staging, they would manually go through the booking flows, note down issues, and report them back. That night, they were our QA team.

The business and marketing folks also jumped in to help the customer service team throughout the day. The call center was flooded, with users frustrated over stuck bookings and system glitches that required manual intervention. So marketing and business picked up the phones and helped sort out the mess.

We had to take the system down completely to perform the migration. Post-midnight was our best bet, fewer bookings, less disruption. But there were a few advance bookings that had already been made.

To handle this, we exported booking details for the customer service team. They personally called the drivers and passengers, giving them pickup addresses and confirming rides, just like the old radio taxi days. Most late-night advance bookings were for airport trips, and we made sure no one missed their flight.

That night, everyone pitched in. No one left early. We helped each other however we could.

And I truly believe everyone there believed in what we were building, that we were on the verge of changing the world.

Of course, the fact that Anthony Tan, the CEO, had a sleeping bag in the office and was literally sleeping next to the exit corridor had absolutely nothing to do with why we all stayed. Nothing at all.

That whole experience was a perfect example of YPIMP, "Your Problem is My Problem", one of our original seven core values before they rebranded them into 4H. Personally, I always preferred the 7 core values, and YPIMP was my favourite.

We weren’t just solving our own problems. We were solving each other’s problems as one.

Next Office

That was just the beginning. As the engineering team grew, so did our challenges, one of the biggest being space.

The office that once felt cozy and just right was suddenly cramped. Desks were squeezed together, chairs bumped into each other, and finding a quiet spot was next to impossible. We had officially outgrown it.

So, we moved. A new office, and with that, a whole new set of adventures.

But that’s a story for another time.

Stay glitched, stay human.

Jibone.