AI is the UI

Peace be upon you, fellow digital traveler.

The AI revolution is upon us. In the near future, AI will be as ubiquitous as computers are today. But this future isn’t about killer robots taking over or sinister machines plotting against their masters. Just as networked computers reshaped the way we work, do business, socialise, and entertain ourselves, AI will introduce a new paradigm for all these things.

But before we get there, we must start at the beginning, the command prompt.

First there was the command prompt

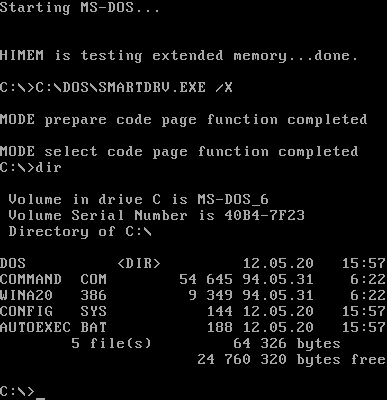

The earliest interface I used to interact with a computer was the ‘command prompt’. A beige plastic enclosure housed a CRT monitor, its black screen sometimes reflecting my face at just the right angle. Within that black mirror, it displayed white or green text, and a small blinking rectangle marking where the next letter would appear.

I was 11 or 12 when I joined my school’s newly formed "computer club." In the early '90s, computers were still expensive machines used mainly for serious business work, and the club was my only chance to experience one.

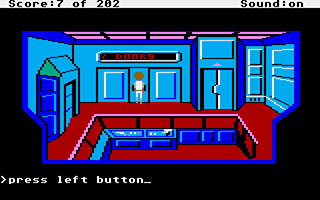

We learned WordStar, Lotus 1-2-3, and basic MS-DOS operations. We were assigned simple tasks like formatting a document in WordStar, or creating a spreadsheet in Lotus 1-2-3. Everyone rushed to finish because once we were done, we had free time. For me, that meant booting up Prince of Persia.

Another favourite was Space Quest, a sci-fi adventure game. Instead of pointing and clicking, you type commands into the prompt—“search the body,” “look at window,” “pick up card,” “open box.” Each command made the character take action, a text-driven interface for an interactive world.

With MS-DOS, UNIX, and other operating systems of the time, the command prompt was the main interface to the computer. You had to type the correct command to get it to do what you wanted.

Want to change directories? — ‘cd’

Want to create a new directory? — ‘mkdir’

Want to list all files in a directory? — ‘ls’ (or ‘dir’ for MS-DOS)

Command prompts were rigid. You had to be precise, no room for ambiguity. To many users, this was cumbersome; you either memorised commands or relied on a manual. For some, it was downright intimidating, full of jargon that seemed alien.

That’s why the arrival of the Graphical User Interface (GUI) changed everything. It made computers accessible by using familiar real-world metaphors; the "desktop," "folders," "documents," and "trash bin." People instantly understood these concepts, and computing was no longer limited to those who could decode cryptic text commands.

The Graphical User Interface revolution

In December 1979, Steve Jobs, accompanied by a team of Apple engineers, visited Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). The visit was part of a deal, Xerox invested $1 million in Apple before its IPO in exchange for allowing Apple engineers to tour PARC and explore its technological innovations.

What they saw changed the future of personal computing.

The Xerox researchers introduced the Apple team to several groundbreaking technologies developed at PARC. Among them was the Graphical User Interface (GUI), a revolutionary way to interact with computers. Unlike the rigid command prompt, the GUI presented a world of visual metaphors: windows, icons, and clickable elements that mimicked real-world objects.

Jobs immediately grasped its potential. He saw how this interface could make computers accessible to the masses. He wasted no time directing his team to integrate similar GUI elements into Apple’s upcoming products, most notably the Lisa and Macintosh computers. Microsoft followed not long after, bringing GUI-driven computing to an even wider audience.

New computer users were introduced to a digital environment that felt familiar. The "desktop" metaphor turned abstract computing tasks into intuitive actions. Instead of typing arcane commands, you could move files into "folders" and delete them by dragging them to the "trash bin." No manuals, no memorisation—just point and click.

This was the dawn of "user-friendly" computing. The GUI made computers approachable, transforming them from tools for specialists into household appliances.

But as we embraced this new interface, we unknowingly locked ourselves into its paradigm. The desktop metaphor became the standard, shaping how we think about and interact with digital systems. Decades later, we’re still inside this invisible prison, constrained by the very interface that once set us free.

The Desktop Metaphor prison

The Graphical User Interface (GUI) as we know it was first developed at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). Xerox, a company rooted in paper-based workflows, photocopiers, printers, and document management, naturally designed its GUI around the concept of paper and documents.

For decades, this is how the average user has understood computers: as digital representations of desks, files, and folders. We "save" documents into digital "folders." We "delete" them by dragging them into a virtual "trash bin." These actions feel intuitive because they mimic the physical world.

But in reality, these are just metaphors, abstractions designed to make computers more "user-friendly." And like all powerful illusions, they obscure a deeper truth.

Just like the spoon-bending monk in The Matrix tells Neo:

“Do not try to band the spoon, that is impossible. Instead, only try to realise the truth. There is no spoon. Then you’ll see that it is not the spoon that bands, it is only yourself.”

As Neo begins to grasp this truth, he is interrupted: "The Oracle will see you now." Ironically, Oracle is the name of a database company, one that deals not with documents, but with data.

The truth is: there are no "documents." No "folders." No "trash bin."

A document is nothing more than a structured series of binary bits, 1s and 0s, etched onto a storage medium, whether it’s a magnetic hard disk, a solid-state drive, or another form of digital storage. Even the act of "saving" is a metaphor. In the early command-line era, the term "save" was seldom used, it is more natural to see the action being referred to as “write”.

And what about deleting? When you drag a file into the trash, and empty it, the system doesn’t destroy it. It simply marks the binary bits as free space, available to be overwritten. The file remains, invisible but recoverable, until it is replaced by something new.

Folders? Another illusion. In the command-line world, they were never called folders, they were directories. A directory is nothing more than a list of files. You don’t “place” a document inside a directory the way you would do in a physical folder. You append it to a list, or remove it from one.

And even a file, the fundamental unit of computing, is just another metaphor, another attempt to impose a familiar structure onto something inherently different. Layer upon layer of abstraction separates us from the raw truth of computing.

That’s why I call the desktop metaphor a prison. It confines us within an interface designed for paper-based workflows, limiting the true potential of digital computing.

Take the concept of folders. In the physical world, a sheet of paper can only exist in one folder at a time. If you want it in multiple folders, you must create copies. Editing one copy does not affect the others.

But this is not a limitation of computers, it’s a limitation of paper.

A digital document doesn’t have to exist in only one place. The same file can be referenced by multiple directories without duplication. Advanced users might recognise this as a symbolic link or an alias. Modern operating systems like MacOS allow documents to be tagged and dynamically grouped into “smart folders” based on metadata, rather than rigid hierarchical structures.

These aren't just features added onto folders, this is a more natural way for computers to operate, but obfuscated away hidden from average computer users.

And this is just one example of how the desktop metaphor limits the true capabilities of our machines. If you look deeply enough, and if you realise that ** "there is no spoon"**, you’ll find countless others.

I could write more on this, but I’ll leave it for a future Code & Codex dispatch. Today’s topic is about the AI revolution.

The AI revolution

There have been attempts to break free from the prison of the desktop metaphor. The modern smartphone interface is one such effort. It introduced new ways to interact with computational devices—pinching, swiping, rotating—suggesting a possible escape from the constraints of the desktop.

Yet, despite these innovations, mobile UI design has plateaued. App interfaces have settled into predictable patterns: the back button in the top left, primary actions neatly lined up at the bottom. We've traded one rigid metaphor for another.

Perhaps we’ve confused familiarity with user-friendliness. If something feels familiar, we assume it’s easy to use. But is that truly the case?

Another attempt at escaping the desktop metaphor came through AR/VR. When Apple introduced the Vision Pro, it promised a new way to interact with computers. But instead of breaking free, it doubled down on the old paradigm. What we got was... floating windows. The same desktop metaphor, just projected into 3D space.

Which brings us to AI, specifically, generative AI and large language models (LLMs). This, I believe, is our best shot at truly escaping the graphical user interface.

Instead of manipulating digital representations of physical objects, icons, buttons, folders, we can now prompt the machine in natural language. No documents, no menus, no rigid workflows. Just intent and execution.

And yet, there's a strange sense of that one has experienced before, a déjà vu.

We started with the ‘command prompt.’ Now we’re back to the ‘prompt.’

The difference is that today, our commands don’t need to be precise. No memorising cryptic syntax. No rigid structure. We can simply describe what we want, and the system interprets it.

But here’s the problem: we're not actually moving towards this vision. The current trajectory of AI is reinforcing the desktop metaphor, not replacing it.

Anthropic’s ‘computer use’ feature lets AI take control of your computer to perform tasks. OpenAI’s ‘Operator’ lets AI use a browser to execute commands. These AI agents are not operating at a lower abstraction—they’re interacting with computers just like we do, navigating the same buttons, windows, and menus.

In other words, they’re just as trapped in the desktop metaphor as we are.

But AI doesn’t need to be confined to our interface conventions. It doesn’t need to click buttons or open files. It could (perhaps should) operate at a much lower level of abstraction.

This is where the generative aspect of AI becomes fascinating. Presently, we’re using AI to generate intermediary artifacts, code, images, text, things that humans are already capable of creating.

Take ‘vibe coding,’ trend for example. We’re seeing people build entire games over a weekend using AI. But AI isn’t generating games, it’s generating code that still needs to be compiled or interpreted.

Why have these extra steps?

Why should AI generate code for a compiler when it could generate the executable binary directly?

And beyond that, why should we even need ‘software’ in the traditional sense? If AI is advanced enough, it could simply do the task instead of generating software to do it. Need a tool for a specific job? Describe it, and AI generates a bespoke solution on the fly.

This is what I mean by "AI is the UI."

AI itself is the interface. There’s no need for icons, buttons, or menus. We return to the minimal prompt, but this time, instead of rigid commands, we use natural language.

Maybe we’ve been thinking about "AI" all wrong. What if it doesn’t stand for Artificial Intelligence, but rather Anthropomorphic Interface, a system that adapts to us instead of forcing us to adapt to it? And if AGI ever arrives, perhaps it won’t be "Artificial General Intelligence" but “Anthropomorphic Graphical Interface”, a system that understands human intent so deeply that it eliminates the need for traditional UI altogether.

The desktop metaphor is a relic of a world where humans had to learn how to use computers. AI presents an opportunity to reverse that equation, to have computers that understand us.

The Chatbot metaphor

Just as the Graphical User Interface (GUI) ushered in the personal computing revolution, making computers accessible to the masses, I believe generative AI has the potential to do the same. It could redefine how we interact with machines, breaking free from the constraints of the desktop metaphor and introducing a new era of computing.

But here’s the catch: are we just trading one prison for another?

If the desktop metaphor trapped us in the abstraction of paper, AI might confine us to the chatbot metaphor, where our interaction with computers is reduced to how well we can phrase a prompt. Instead of being limited by icons and folders, we might soon be limited by language itself, bound by grammar, syntax, and how precisely we can articulate our intent.

Something to think about. Until the next dispatch,

Stay glitched, stay human.

Jibone