Import Tariffs for Code

Peace be upon you, fellow digital traveller.

If you are reading this somewhere in the future, know that this was written during the Trump tariff fiasco. In early April 2025, Trump imposed a series of steep protective tariffs affecting nearly all goods imported into the United States. One particularly symbolic measure, dubbed the "Liberation Day Tariff," triggered a chain reaction in the global free trade economy.

In this Code & Codex, we’re not here to dissect trade wars or economic fallout. Instead, this is a thought experiment: what if the same spirit of "protectionism" were applied to code and software?

Like many other software engineers, I made a half-serious joke about a code import tariff.

Code Base Liberation Day!

We must impose an npm import tariff to reduce our reliance on foreign code.

Bring back the code. Write the ISO date formatter from scratch.

Make JavaScript Great Again.

Ever since I posted that joke, a thought has lingered in my mind: what if it were possible to actually tariff code? What if importing foreign code into our codebases came with a monetary penalty? In such a world, "tech debt" could literally mean financial debt—owed straight to the government.

I know these ideas are far-fetched, and the likelihood of such a world emerging is close to zero—but not quite impossible.

Software has become democratised. Anyone, from any country or economic background, can create it. I’m not talking about AI-generated software—this was true even before AI began mass-producing code. The only real barrier has always been access to a machine that can compile and run the ideas they write.

Even though anyone can create software, no one builds software entirely alone.

I, pencil

"I, Pencil" is a classic essay written by Leonard E. Read in 1958. It tells the story of a humble pencil and traces the journey of its creation.

Not a single person on the face of this earth knows how to make me

A simple wooden pencil, with an eraser at one end, yet no single person on earth could make it alone.

Paraphrasing from the essay; the pencil starts cedar wood, cut down by loggers using equipment crafted by countless others. Even further upstream, steel is needed for the saws, pulling in thousands more into the story of this simple tool.

The pencil’s core, what we call "lead", is made of graphite, mined by yet more hands, using mining equipment fashioned by others still.

The eraser comes from rubber, drawing chemists, plant workers, and a whole chain of unseen contributors into the pencil’s making.

The essay dives deeper into each step, but its core message is simple: there is no central planner orchestrating the making of a pencil. It comes into being through the ‘invisible hand’ of the market. This is the power of the free market.

The term ‘invisible hand’ was coined by the 18th-century economist and philosopher Adam Smith, in works like The Wealth of Nations. He used it to describe how individuals, by pursuing their own self-interest, unintentionally contribute to the collective good, without any central planning.

Invisible Hands in Software making

The same could be said for software. No single person creates it entirely on their own. Even the simplest "Hello, World!" program carries the fingerprints of countless programmers.

Here is an example of a ‘Hello World’ program in C:

# include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello, World!\n");

return 0;

}

You might think you wrote it all yourself, but you didn't. The #include <stdio.h> statement pulls in a header file from the C standard library, offering you core input/output functionality. The function printf you used? Crafted by others, long before you typed your first line.

Before your program can run, it must be compiled into machine code—likely using a standard C compiler like GCC, itself a creation of countless programmers. Even the humble text editor you typed your code into rests on layers of libraries and frameworks built by unseen hands.

You are not alone in writing that simple ‘Hello World’ program.

Just as Leonard E. Read showed how invisible hands brought the pencil into existence, invisible hands shape our software. But there's a twist: in open-source software, it isn’t the free market or the competition of buyers and sellers that drives these hands.

Protectionism in software

Open-source has democratised software. It broke down barriers allowing individuals, students, hobbyists, and people from all socio-economic backgrounds to access the libraries and tools needed to build the software they envision. While skills, time, and access to a computer are still required, these resources are more attainable today than ever before.

Open-source software and open protocols have made the digital world accessible to the masses, globally.

But what if that wasn’t the case?

To some, the open-source movement itself is a fight against protectionism in software.

Big Tech may want everyone to use the software they create, but not necessarily for everyone to make their own. They prefer you to use their products on their terms, with them controlling the platform, the rules, and your access to it. Even when they give you the tools to make your software, they’ll make sure your apps only run on their platform, that they control.

Protectionism in software is already here in several forms: proprietary (closed-source) software, restrictive licenses, and software patents that limit the freedom to create, not by technical barriers, but by legal ones.

Platform monopolies are another form of digital protectionism. Apple’s App Store, for example, famously restricts app distribution: there’s no way to install an app on an iOS device without going through the App Store (unless you jailbreak the device).

But what if there’s an even more nefarious future?

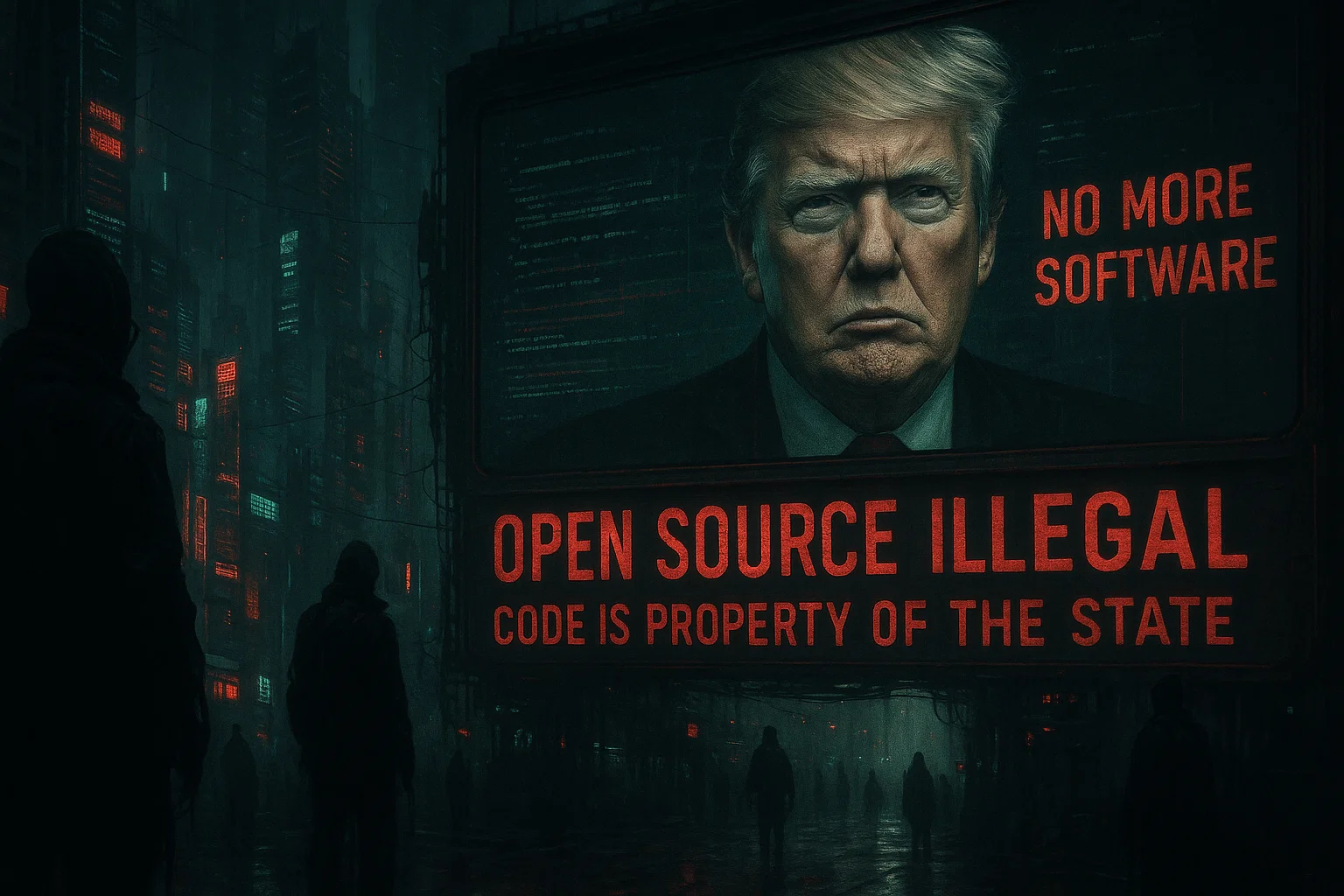

Imagine a world where a powerful nation, one that dominates the software industry, decides to lock down its code entirely. Open-source becomes illegal. All code written within the country is declared the property of the state.

In this future, open collaboration is a crime, and creativity is taxed at the source. Code would no longer be a shared inheritance, it would be a controlled commodity. And every npm install would come with a price tag, not just in dollars, but in freedom.

When code is no longer free to share, innovation doesn’t just slow, it decays.

Combating Software protectionism

There are several ways to prevent such a scenario from ever taking root. The best way to combat protectionism in software is through a mix of technology, culture, and community.

There’s no single solution, only an ecosystem of counter-forces.

First, and obviously, is supporting open-source projects. The stronger the support through usage, code contributions, and funding, the weaker the hold of closed proprietary ecosystems.

Second, we must support and use open standards and interoperable protocols. Open standards, like HTTP, HTML, and JSON, are public rules for how software communicates. Anyone can build their own implementation without being tied to a single company’s platform.

Third, we must promote data portability. Users should own their data. If someone decides to leave Facebook for a new platform, they should be able to export all their data and take it with them. This is already possible today, thanks to the push for data rights, but it’s still messy.

Fourth, we need to build more federated and decentralised alternatives. Instead of giant centralised platforms that own everything, we need many small, interconnected systems built on open standards and true data portability. In this model, users own their identity and data, and can freely move from one platform to another without friction.

Other fronts in the battle against software protectionism include raising awareness, fostering strong developer communities, and pushing for legal reforms.

While it’s not yet a formal movement, “Freedom Tech” embodies these values, technology that empowers the individual, not corporations or governments. It’s something worth keeping a close eye on.

Imagine freedom, written not in law, but in code.

Stay Glitched, Stay Human

Jibone.